The word Panchanga or Panchangam, an many of you would know, refers to the Hindu calendar and is a combination of two words ‘pancha’ and ‘anga’ meaning five parts. The five parts are vara, tithi, karana, nakshatra and yoga.

Indian Astronomy & Modern Astronomy – A key difference

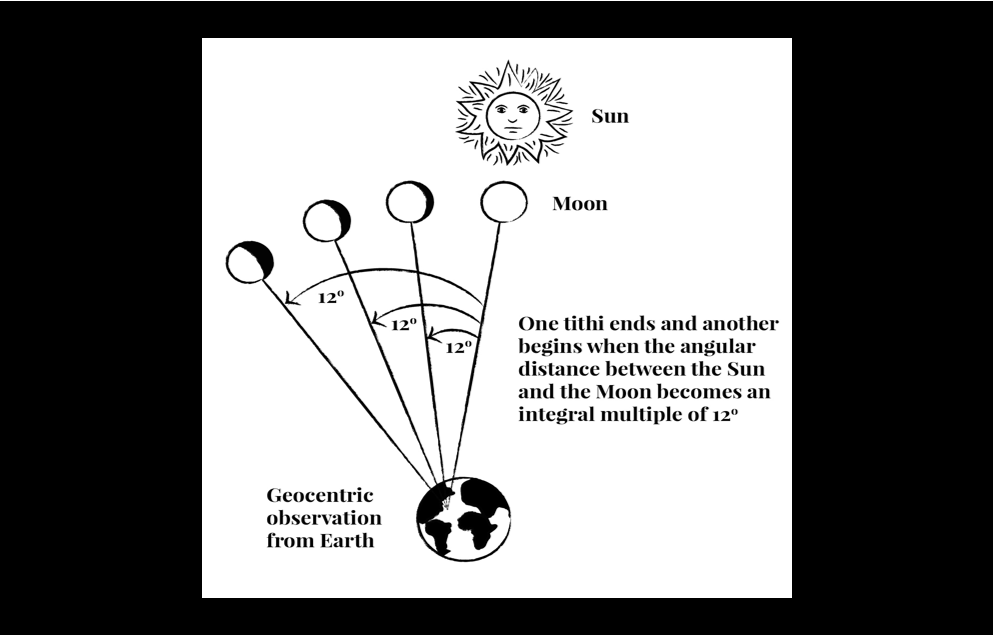

The key difference between modern day astronomy and ancient Indian astrology. While modern astronomy has established that the earth revolves around the sun, the Indian astrology follows a geo-centric model, where the celestial bodies in the sky are taken as moving bodies but the earth is presumed to be fixed. So, the movements of the sun, moon and other planets are studied keeping the earth as a fixed point. So, when we say the sun moves across the sky, what we mean is that the Sun is seen to be moving across the sky as viewed from the earth.

Vara

Vara refers to the week day. Following the Greeks, ancient Indian astronomers chose to adopt a 7-day week (why does the week have 7 days?), and the days of the week have been named after the Sun, the Moon and five planets including Mars, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury and Saturn. Thus, we have the ravivara, somavara, mangalvara, budhavara, guruvara, the shukravara and the shanivara.

Unlike the Gregorian calendar, where the day is counted from midnight to midnight, the day according to the Panchang is from sunrise to sunrise. However, the time of the sunrise changes slightly everyday as the relative position of the earth in its orbit vis-à-vis the sun keeps changing. As a result, the duration of the day is not always 24 hours.

And as we measure the day in hours and minutes, in Indian astrology, the duration of the day is measured in ghatikas or nadis, and vighatikas. A day comprises 60 ghatikas; each ghatika of 24 minutes duration.

You might note that it is the exact inverse of 24 hours of 60 minutes duration each that we follow today.

Tithi

The second element of the Panchanga is the tithi. While vara depends on the movement of the sun, the tithi is decided by the movement of the moon. A tithi refers to one lunar day. A lunar month from new moon to full moon is divided into two parts called paksha. The brighter half or the period of the waning moon is called the Shukla paksha and the darker half or the period of the waxing moon is called Krishna Paksha.

Each of the two pakshas has 15 thithis. The shuklapaksha starts with the first day of the waning moon called pratama or pratipada and ends with the 15th day, which is the full moon or Purnima. The Krishnapaksha starts with the first day of the waxing moon and ends on the 15th day, which is the no moon day or Amavasya.

In all, there are 30 tithis in a lunar month.

Now, the duration of a tithi is decided by the movement of the moon with respect to the sun. It is the time that the moon takes to move 12 degrees away from the sun, as seen from the earth.

But why is the distance being measured in degrees?

Here’s why. You may remember from the basic astronomy we learnt at school that the celestial bodies in our solar system move in a fixed but elliptical orbit. And we on earth see these bodies move in an arc across the sky above us. So the only way distances can be measured on an elliptical orbit is by measuring it in angles or degrees.

As with a solar day or dina, the duration of the tithi also changes. This is because the sun and the moon are travelling at varying speeds and the time taken by them to be separated by 12 degrees keeps changing. So, a tithi can last anywhere between 19 and 26 hours. And you can end up having more than one tithi, or an incomplete tithi in a 24-hour day.

Karana

The third aspect of the Panchanga is the Karana. A Karana is half a tithi. In other words, it is the time taken for the moon to move 6 degrees away from the sun. In all there are 11 Karanas of which 6 are considered benefic and the remaining 5 are malefic.

Both Tithis and Karanas are vested with good and bad attributes. So some tithis and Karanas are considered auspicious while some others are considered inauspicious.

Yoga

Yoga is another division of time in the panchanga. The word yoga as you’d all know means union or alignment. The yoga mentioned in the Panchanga refers to the interactions between the sun and the moon, the two key celestial bodies whose movements are tracked in our calendars.

Mathematically speaking, the yoga of the day is obtained by adding together the positions of the sun and the moon as seen from the earth, in angles or degrees. The sum obtained is then divided into 27 parts, each of which is a yoga. Each of these 27 yogas is given an attribute, some good and some bad. The yoga prevailing at sunrise is taken to be the yoga of the day.

Yoga is important from the point of view of casting a birth chart or a kundali and also for fixing the appropriate time to carry out specific activities. The yoga in which a person is born is believed to decide his or her nature and also if she is likely to be lucky, wealthy and so on. As mentioned earlier, Yoga also helps fix the muhurta or the right time to carry out a specific action.

Nakshatra

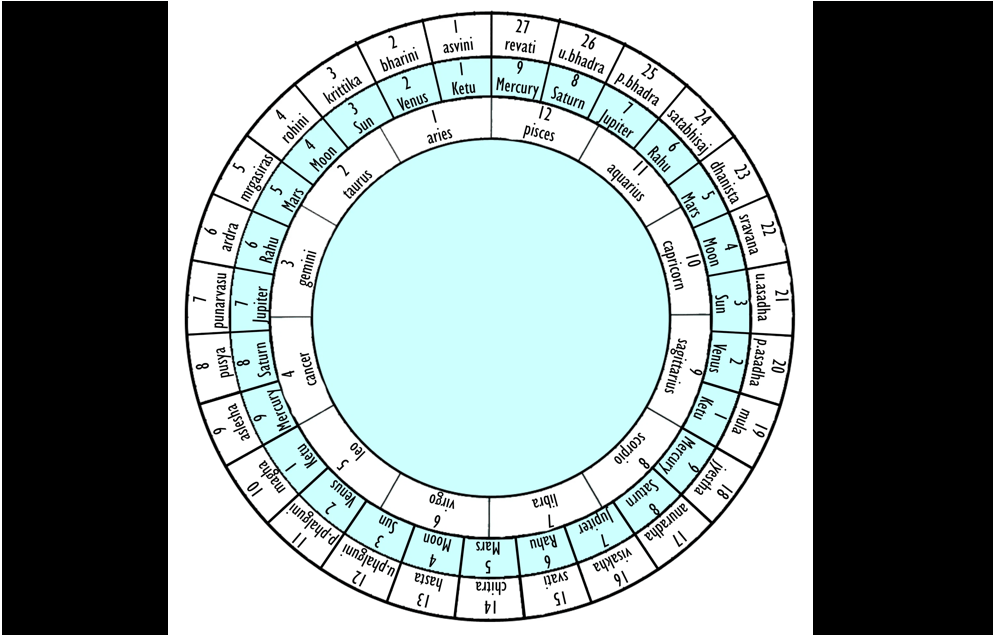

Nakshatras are a very ancient Vedic concept where the moon’s path in the sky is divided into segments of constellations. We all know the moon rotates around the earth. Its movement in the sky is traced, and depending on its position, its orbit is divided into 27 arcs into which fall various constellations. In other words, the nakshatra system is used to plot the moon with respect to the other stars in the sky (why are there 27 nakshatras in astrology?).

Although, nakshatra is commonly understood as a star, in astrology, it actually refers to a constellation of stars. The particular constellation where the moon is found is identified by a prominent star in that constellation. And so we have the Ashvini, Chaitra, Revathi, Jyeshta, Vishaka nakshatras etc.

In Indian mythology, the moon is believed to chase the nakshatras who are imagined as his wives. To the ancient Indian astronomers, however, these nakshatras were a kind of unchanging celestial markers. These markers enabled the astronomers to keep track of the moon’s movement across the sky.

As with yoga, the nakshatras are also believed to possess certain specific attributes. So a person born in a particular nakshatra is believed to possess certain specific qualities.

Lunar tilt of our calendars

Of the above five limbs of the panchanga, nakshatra, tithi and karana are based on the movement of the moon while only the vara is based on the movement of the sun. Yoga, of course, takes into consideration the orbits of both the sun and the moon. So we find that 4 out of the 5 elements of the panchanga are based on the moon’s movement, making our calendars a largely lunar calendar.