Science may have conquered various myths relating to our lives in the course of human evolution, but there is still one aspect of our existence that science is yet to decipher and give us convincing answers for….and that is death….and what happens after!

World over, cultures have tried to explain the horrifying reality called death using mythology. Some, like the ancient Egyptian civilization, left such a strong trail of their belief in afterlife in the form of lofty pyramids and grand tombs that have survived 3000 odd years to tell us the dead man’s tale.

Afterlife and life thereafter….

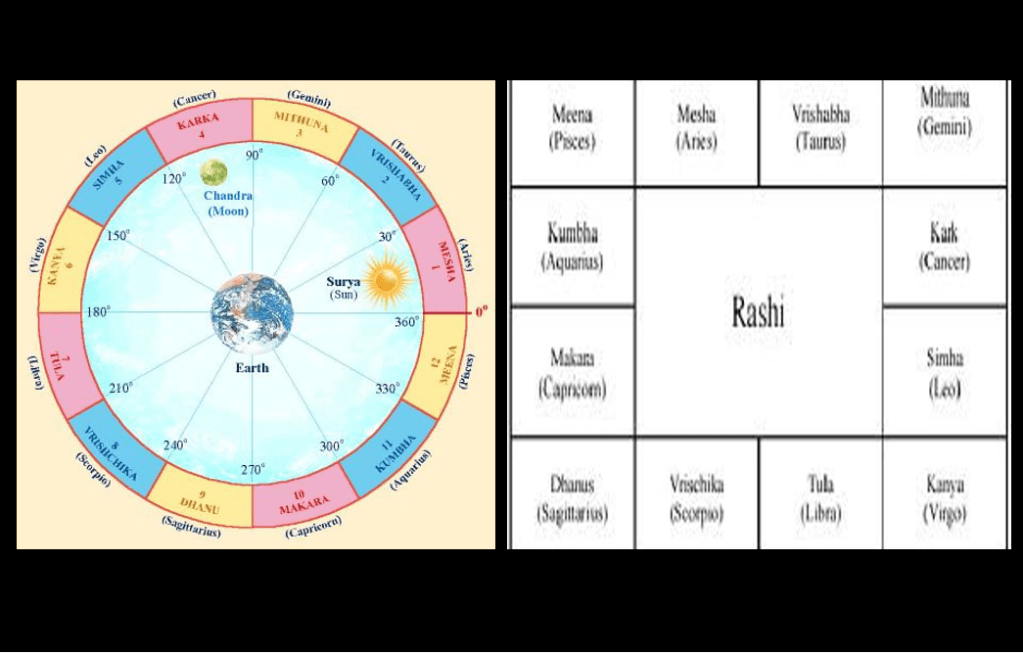

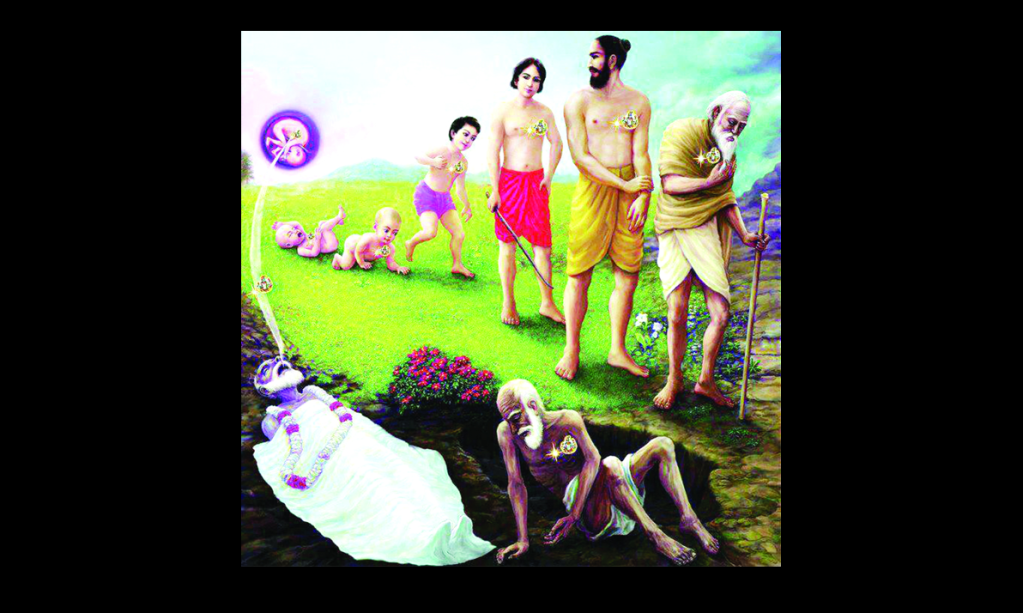

Just as the ancient Egyptians, Indians too believe in afterlife. In Indian thought, the deceased enters the heavens (Swarga) or hell (Naraka) depending upon the accumulated reward of his good deeds (punya) and bad deeds (paapa) but does not become a permanent resident there. He/She spends a short while there till his/her accumulated rewards/penalties are exhausted. Thereafter, the deceased takes on another body and life (not necessarily human) to be born again on earth. The cycle of births and deaths continue till one day, having exhausted all its karma (fruits of its actions), the life attains moksha (or birthlessness).

How the beliefs and rituals evolved through the Vedic and Puranic times….

While the Vedic texts do express the ancient man’s fears and beliefs around death, their key intent seems to have been to ensure the safe transport of the dead persons to the land of their forefathers (pitrulok or yamalok as yama was considered the first man to die). Towards this end, they lay down meticulous specifications for conducting elaborate funeral ceremonies.

Although the Rig Veda does express the desire for the dead to return to earth taking on a new body, it does not deliberate much on the concepts of paapa/punya and accumulated (sanchita) karma. These ideas seem to have evolved later, and are dealt with in detail in the Puranas. The Puranic texts that were composed later, thus discuss at length the various expiatory rites. These rites, if performed during the lifetime of an individual, promise to alleviate the toils faced by the aggrieved soul on its journey to pitruloka and also ensure his/her next birth in a better stratum of the society.

Some of these rituals seem to have their basis in the idea of the gift economy (dana), created to sustain the livelihood of the priestly class. The texts prescribed several danas in the form of cows, umbrellas, pots and vessels (in gold and silver) to be made to the Brahmins, who had no means of income of their own, but lived on the charity and magnanimity extended by the other three varnas (the Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras). Thus, we find the idea of the benefits arising from making dana to the Brahmins gaining strength through the Puranic times.

While the Vedic people offered the things that they believed the dead person would need on his upward journey as oblations into the fire, from the Puranic age, these items have come to be donated to the Brahmins who collect them on behalf of the dead persons.

The period of the Puranic age that coincides with the Gupta era saw a further evolution of the ideas around afterlife with increased emphasis on certain beliefs that the priestly class shared with tribals.

Vijay Nath in her book, Puranas and their Acculturation says that the need to bring more and more peripheral lands under farming during the Gupta era led to the grant of these lands to Brahmins. The movement of the priestly class to the countryside put them in close contact with the tribes that occupied the lands identified for agricultural development. This resulted in the exchange of several ideas between the two communities, including the elaboration of the tribal ideas of hell and retribution in the Puranas.

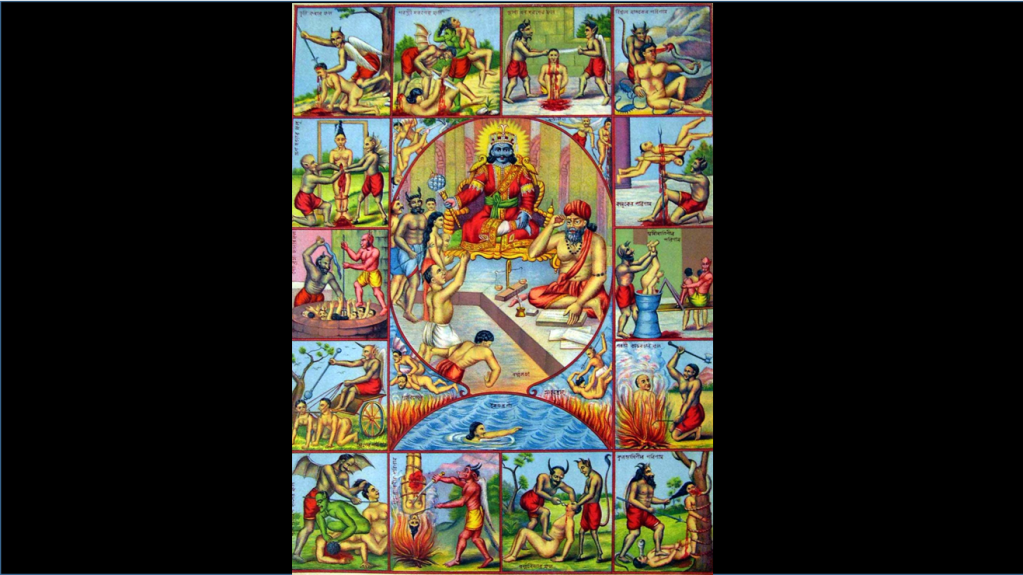

The Puranas talk about some 100 different types of hells (Naraka) specific to the sins committed by the deceased. These texts present a picture of these purgatories in great graphic detail using elaborate imagery and supporting mythology, and seem to have been used as deterrents against deviation from tradition and norms in the fast expanding society.

The journey of the lone soul…..

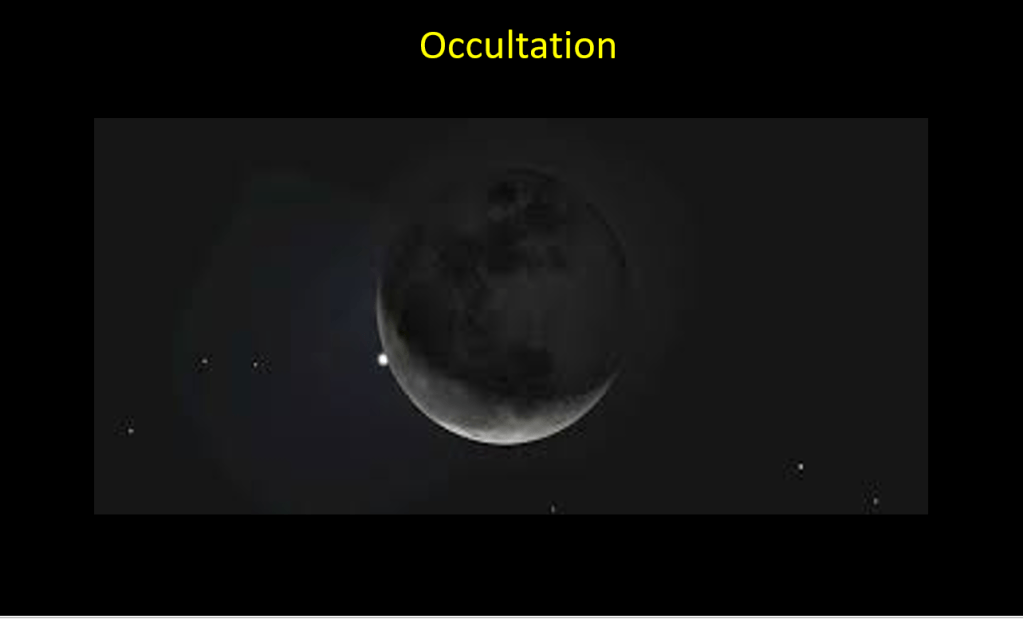

According to the Garuda Purana, the deceased’s soul is believed to set forth on a long and arduous journey to yamaloka pulled away from the memories of his surviving kith and kin by yama’s assistants. The Purana gives a detailed account of the soul’s journey and the travails it faces along the way, before it reaches yamaloka where its paapa/punya accounts are maintained.

This journey of the soul is supposed to take a whole year during which time it experiences hunger and thirst just like the living. To satisfy the needs of the soul, the heir of the deceased (or any other karta) is expected to offer it a rice ball (pinda) every month during the course of its year-long journey. Feeding on these rice balls, the soul gradually regrows a part of the body every month, and by the end of the year when it reaches yamalok, it has regrown its complete body. At the yamaloka, judgement is awarded and the soul begins the process of its re-entry into the mortal world, all over again.

Today, to many of us, these rituals and the mythology behind them may seem macabre and belonging to a dark, primitive past. But the truth is that today, even as we talk about the colonization of outer space, we don’t have better answers for the two primal questions that have nagged mankind over eons – where do we come from and where do we go? Here, mythology scores by giving you an answer that is as good as any….